by Rebecca Whitman Koford

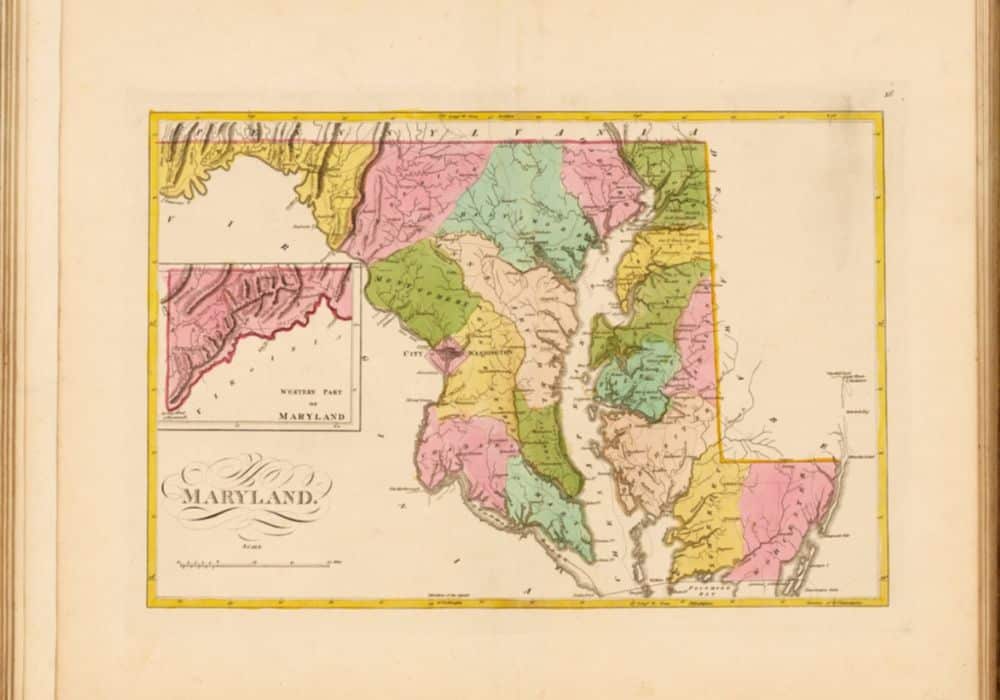

To walk in Maryland is to walk in history. The state’s rich coastal areas—from the Atlantic to Chesapeake Bay to the Potomac—attracted early colonizers. Major industries persisted throughout the centuries: shipbuilding, fishing, tobacco-growing, subsistence farming, and iron production. Because Maryland sits on the border of North and South, it’s been a witness to important military and cultural conflicts. Whether your Marylander family has lived there for decades or migrated west through the Great Valley Road or Cumberland Gap, this guide will help you trace your roots in this historic state.

State History

Indigenous groups in what is now Maryland included both Algonquin-speaking tribes (Piscataway, Conoy, Nanticoke and Patuxent) and Iroquois-speaking (Massawomeck, Susquehannock and Tuscarora). Few records document Native people, especially those who lived in Colonial-era Maryland. Famous explorer (and leader of Virginia Colo-ny) John Smith sailed up Chesapeake Bay in 1608.

In 1632, Englishman George Calvert, Lord Baltimore, received a charter for a colony called “Terra Mariæ.” He died before the colony came to fruition, but his sons Cecilius and Leonard made it a reality.

In 1634, 200 settlers known as “Adventurers” sailed aboard the Ark and the Dove and founded St. Mary’s City. Calvert (who had recently converted to Catholicism) envisioned Maryland as a safe haven for English Catholics. The name “Maryland” comes from King Charles I’s Catholic wife, Henrietta Maria. The Maryland Assembly passed an act allowing religious freedom (at least for most Christians) in 1649, but a council largely made up of Puritans repealed it just a few years later. Ample land encouraged settlement, with Lord Balti- more promising acres to each settler who brought “able

men.” The allotment was later expanded (albeit at a lesser amount) for married settlers, servants, widows and children under age 16. Indentured servants became a significant part of Colonial Maryland’s population. Their service was tied either to individual contracts for a set number of years or participation in the headright system. Some later servants were convicts from England, angering local residents.

Because indentured servants were contracted only for certain lengths of time, the enslavement of Black people from Africa proved more lasting and profitable. The growth of slavery—actively encouraged by lawmakers—eventually made the indenture system obsolete. And though the Maryland legislature passed laws protecting some rights of indentured servants, it ignored those of enslaved people. Sectarian tensions culminated in Protestants ousting the Calvert family’s proprietary o ̄cers. Maryland became a Crown colony in 1691, with Anglicanism as the established church. The Calverts regained control of Maryland in 1715—after converting to Protestantism.

In 1706, Marylanders opened the Port of Baltimore, named after Cecilius Calvert, Lord Baltimore. It grew to be one of the largest ports in the Thirteen Colonies, and the town of Baltimore was established in 1729.

Disease and land disputes caused Native populations to rapidly decline throughout the first 100 years of white settlement. By the 1740s, most extant groups moved west or north to join the Six Nations (or Iroquois Confederacy). The Piscataway are the largest group in the state today.

The Maryland-Pennsylvania border, established in 1767, is better known as the Mason-Dixon Line, reflecting Maryland’s historical status at the boundary between North and South. Years of disaffection and grievances over religion, taxes, and restrictions on settlement and trade led colonists to join the growing independence movement. The Maryland General Assembly approved its own constitution in 1776, and some 28,000 Marylanders served in the American Revolution. In the Battle of Brooklyn, Maryland troops repelled the British and allowed Washington’s army to retreat. Their bravery led Washington to refer to them as the “Old Line,” leading to the state’s nickname of “Old Line State.” Maryland became the seventh state to ratify the Constitution, and contributed about 69 square miles to the new District of Columbia along its southern border.

The young state saw considerable action during the War of 1812 against the United Kingdom. Seminal events there included the Battle of Bladensburg and the bombardment of Fort McHenry near Baltimore (which inspired Francis Scott Key’s “The Star-Spangled Banner”).

Improvements in transportation encouraged some Marylanders to move west through the 1800s. The Cumberland Road (or National Road) started on the Potomac River in Cumberland, Md., and reached Wheeling, Va., in 1818. Construction on both the Chesapeake and Ohio Canal and the famous Baltimore and Ohio Railroad began in 1828. Maryland—Baltimore, in particular—became a popular destination for immigrants. Lauded for its religious tolerance, Maryland attracted Germans from Pennsylvania and Catholic Irish immigrants (especially after the mid-1800s). Early Jewish migrants were also drawn to the state; the Lloyd Street Synagogue in Baltimore (built in 1845) is one of the oldest in the United States. From 1820 to 1850, Baltimore was the second most-populous city in the United States, behind only New York City.

Maryland maintained both its status as a slave state and its membership in the Union during the Civil War. Its residents had split loyalties: Some 63,000 troops served the Union, but about 21,000 joined the Confederacy. The Battle of Antietam (which took place near Sharpsburg, Md.) remains the bloodiest in US history.

Near the end of the war, Maryland’s new constitution ensured that slavery was abolished. Many African Americans left the Jim Crow South for the state, particularly during the Great Migration of the early 20th century.

Return to top

Vital Records

Some counties instituted vital registration as early as 1649. From 1692, Anglican Church parishes (representing the establish church in the colony) recorded vital events regardless of religion, but coverage is inconsistent. Baltimore City began vital record keeping in 1875. But the rest of the state did not follow until 1898. Compliance was inconsistent until around 1914.

The Maryland State Archives are the primary repository for historical vital records, including indexes. Some marriage and death records are available directly from their website; use the “Reference and Research” tab at the “Guide to Government Records” page. The Vital Statistics Administration(part of the department of health) holds recent records: birth records less than 100 years old and death records less than 10 years old. Records within those time frames are restricted.

Marriage records were kept regularly at the county level from early on, then at the state level starting about 1777. The state archives hold marriage certificates up to 2013— see the website for links to marriage indexes.

Return to top

Census Records

As one of the original Thirteen Colonies, Maryland has been documented in each federal census since 1790. Returns for some early years (as well as for 1890) are missing or destroyed. Surviving records through 1950 are widely available on the major genealogy websites. Those researching the enslaved should check the slave schedules, taken as part of the 1850 and 1860 censuses. Maryland took its first and only local census in 1776.

That enumeration often named all members of a household, including African Americans. Another count was taken in 1778 to tally which males over age 18 signed an oath of fidelity. Images and transcriptions of surviving Colonial records have been published in Gaius Marcus Brumbaugh’s two-volume Maryland Records: Colonial, Revolutionary, County and Church from Original Sources (Genealogical Publishing Company). That publication is searchable on Ancestry.com, and the Maryland State Archives have digitized an index.

Return to top

Land Records

Maryland is a state-land state, meaning land there was administered by the colonial or state government. Deeds describe tracts according to the metes-and-bounds system, creating a kind of puzzle-

piece patchwork. Tenant-based land grants, part of the headright system, generated several documents: a warrant, a survey, quit- rent receipts, and (eventually) land patents. Fortunately for

researchers, many of these records have survived. They’re held by the Maryland State Archives. MDLandRec, a free site published by the Maryland State Archives, has an impressive collection of digitized records. You’ll need to sign up for a free account on the site to access them.

Return to top

Immigration and Naturalization Records

Passengers weren’t generally documented in manifests until 1820. After that year, passenger lists (technically, customs lists) for the port of Baltimore have been digitized on web- sites such as FamilySearch. Immigrants who naturalized before October 1906 could have done so at any courthouse; after that, they submitted paperwork only in federal courts. Check voter registrations (extant at most county courthouses or at MSA), which asked for year of arrival, naturalization year, and court of naturalization.

Return to top

Religious Records

As stated in the vital records section, local Anglican parishes were charged with keeping vital records beginning in 1692. Many indexes have been published about Maryland records for these and other denominations, including: Roman Catholics, non-Anglican Protestants (especially Episcopalians and Lutherans) and Jews. MSA includes a religious records finding aid among their special collections.

Return to top

Maryland Genealogy Resources

WEBSITES

Archives of Maryland Online

Cyndi’s List: Maryland

Digital Maryland

FamilySearch Research Wiki: Maryland

Linkpendium: Maryland

MDGenWeb

MDLandRec

GENEALOGY BOOKS AND PUBLICATIONS*

Maryland, A Middle Temperament: 1643–1980 by Robert J. Brugger (Johns Hopkins University Press)

Maryland Records: Colonial, Revolutionary, County and Church from Original Sources by Gaius Marcus Brumbaugh, two volumes

NGS Research in the States Series: Maryland by Rebecca Whitman Koford and Debra Hoffman (National Genealogical Society)

Settlers of Maryland, 1679–1783, fi�ve volumes by Peter Wilson Coldham (Genealogical Publishing Co.)

ARCHIVES AND ORGANIZATIONS

Enoch Pratt Free Library

Maryland Center for History and Culture

Maryland Genealogical Society

Maryland State Archives

National Archives at Philadelphia

University of Maryland Special Collection

*FamilyTreeMagazine.com is a participant in the Amazon Associates Program, an affiliate advertising program. It provides a means for this site to earn advertising fees, by advertising and linking to Amazon and affiliated websites.

Return to top